Reading Time: 7 Minutes

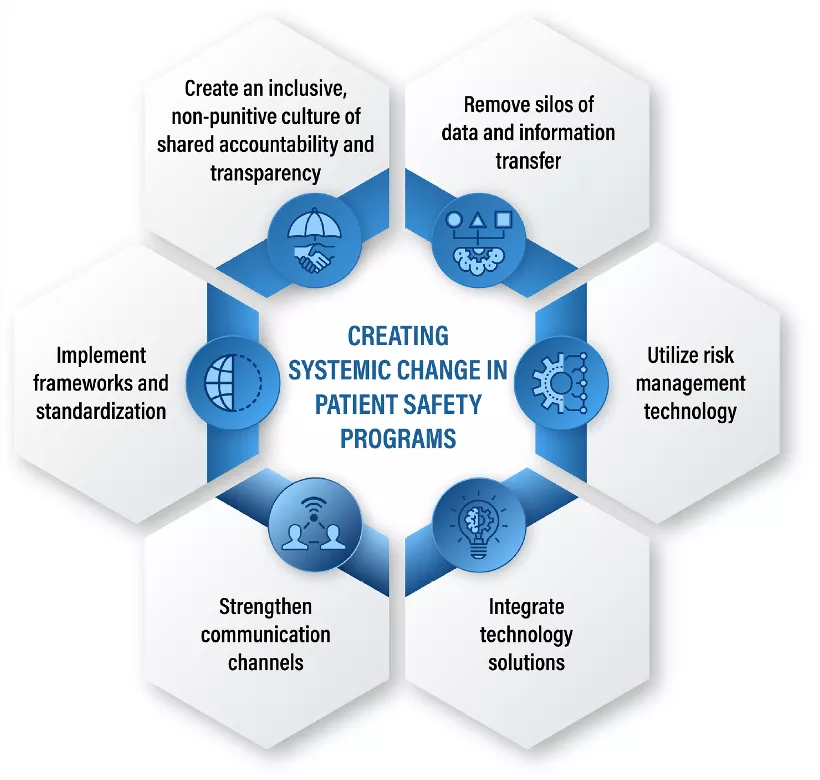

There are many reasons for the uneven progress of patient safety programs, but one common theme is a general lack of strategic approaches that connect people, culture, processes, incentives, and technology. A concerted approach that integrates six areas of focus can enable healthcare organizations to align, focus, and engage workers across the care continuum to improve patient safety. Despite the challenges, there are tremendous opportunities for organizations that can effectively implement technology to support patient safety cultures and processes, and vice versa.

The Rise of Patient Safety

Published in 1999, the Institute of Medicine’s To Err is Human elevated the discussion around patient safety by estimating that medical errors likely contributed between 44,000-98,000 deaths per year. This stark assessment provided an understanding of the true scale and scope of patient safety issues facing the healthcare industry. According to the Patient Safety Network’s (PSNet) Patient Safety 101 Primer, “Most consider its publication to represent the beginning of the modern patient safety movement.”

The correlation of medical errors to deaths led to the Joint Commission’s issuance of new patient safety guidelines in 2003, the adoption of additional patient safety-focused practices such as deploying hospitalists and relying on processes like the use of checklists to reduce preventable healthcare-acquired infections (HAIs). As the practice of patient safety became more visible and formalized, the industry devoted increasing resources to growing the science of reducing adverse events (patient harm that arises as a result of medical care).

Progress is Uneven, Momentum Stalls

While these efforts, collectively, have made identifiable progress, it is unclear if that will continue at the same rate. The Patient Safety 101 Primer notes:

“Despite these successes, rates of preventable harm among patients remain unacceptably high, and new challenges have emerged that have hindered efforts to improve safety. One of the main new challenges to the safety field is the information technology revolution, which has transformed the day-to-day practice of medicine but has not always resulted in safer care.”

It is also apparent that progress has not been uniform. Disparities persist across specific populations, and progress has been uneven across service lines and various ethnic and socioeconomic groups. Nearly 40 percent of indicators broken down by income and race/ethnicity, for instance, indicate that people living in lower-income households receive worse care compared to those living in high-income households.

Read Next: How to move beyond the patient safety status quo

In addition to stubbornly high rates of preventable harm and non-equitable disparities, patient safety efforts are limited by yet another factor. The Patient Safety 101 Primer points to challenges with measurement as a significant obstacle. “The safety field continues to be limited by a lack of standardized measurement criteria, especially for diagnostic errors, which have not gained as much attention as other aspects of safety despite being quite common,” the report observes.

Unconnected Approaches — The Dangers of Solo Firefighting

Part of the challenge stems from the fact that many different groups historically tried to individually tackle their slice of the problem without a coordinated, overarching strategy. This leads to inconsistent approaches across locations and between departments. Ultimately, it hinders decision-making capabilities at the leadership level.

Illustrating this conundrum, Don Berwick, the former administrator for CMS and CEO of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, delivered a speech in 1999 on the failings of American health care, in which he recounted the story of the 1949 Mann Gulch fire in Montana. Wag Dodge, the commander of a team of parachuter firefighters on the scene, led a group into the midst of the blaze, which quickly engulfed the crew. To survive the inferno, Dodge lit an escape fire, lay down in the burned-out area, and emerged virtually unharmed. Despite his efforts to get everyone else into the “safe zone,” the firefighters ran past Dodge, ignoring him because they had not been properly introduced to him and didn’t understand the team’s goals and leadership dynamics. Ultimately, 13 members of the team perished in the fire.

Read next: How to track COVID-19 vaccinations

The tragic failings of this incident, Berwick maintained, underscored the importance of everyone working together and, more specifically, the ability to think coherently and act together. Dodge’s lack of effective communication limited his credibility and caused his team to ignore his pleas. Berwick maintained that the Mann Gulch fire story illustrated what was happening in health care, where a lack of transparency, openness, and measurement led to unnecessary mortality and suffering.

A solo firefighter is less impactful than a coordinated team. Likewise, patient safety challenges will require a fully coordinated attack to make a difference.

Pivoting to Zero Harm

Other industries, most notably aviation and nuclear science, have been largely successful in adopting a zero harm approach to eliminating the same type of systemic mistakes that can lead to catastrophic results. This approach designates organizations that have successfully integrated enterprise-wide measures to combat errors as “high reliability organizations.” However, simply adopting that term in a healthcare setting can prove challenging.

“Ask 10 healthcare leaders if they’ve heard of high reliability, and it’s almost certain all 10 will say they have. Ask those same 10 to define high reliability, and things get interesting.

Many healthcare leaders have a genuine interest in high reliability but often do not know exactly what it means or how to incorporate it among their organization’s other priorities. They just know it sounds right to say their organization is working to 'get to high reliability,' and they hope it will be the silver bullet that solves all problems. Unfortunately, the term ‘high reliability’ can become a buzzword when used without understanding what it is. Employed this way, it may sound great but lack substance—all sizzle and no steak.” — Zero Harm is the Goal, Patient Safety & Quality Healthcare (PSHQ) by Erin S. DuPree, MD, FACOG

Can the Healthcare Industry Reach Zero Harm?

Survey results from the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare cast doubt on the industry’s preparedness for this approach. Although the overwhelming majority of respondents (96%) describe themselves as “fully committed” to zero harm, more than 1-in-10 said they don’t have the required tools and training to effectively implement it.

Read next: How to select the best patient safety solution for your healthcare system

In part, this is due to the number of stakeholders involved, each taking a siloed approach (with siloed systems) at patient safety. The report RCA2 Improving Root Cause Analyses and Action to Prevent Harm by the National Patient Safety Foundation explains how this effort needs to be supported enterprise wide. “The success of any patient safety effort lies in its integration into the fabric of the organization at all levels,” it states. “This cannot happen without the active participation of leaders and managers at all levels.”

To move the healthcare industry toward the goal of zero harm, approaches need to be employed that connect segmented location data and open up participation among different clinical and functional groups. Additionally the approach requires a systems perspective that emphasizes the “why” and root causes of adverse events, and fosters a continuous learning environment.

Better Data, and More of It

Authors Zane Robinson Wolf and Ronda G. Hughes suggest in their book, Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses, that near misses may occur 300 times more often than adverse events. If near misses share common root causes with adverse events, but the quantity of data is 300X larger, a much more robust analysis can be done if that data is included.

The article Near Misses and Their Importance for Improving Patient Safety by Abbas Sheikhtaheri, points out that enlarging the data set is not the only benefit to incorporating near miss data. “Additionally, the reporters of near misses are not at the risk of blame, shame or legal litigation. Therefore, this may positively influence the staff willingness to report these incidents without any fear,” he notes.

Better data, collected from unified sources of information, can help capture and connect risk data in a way that surfaces the most critical information, so all stakeholders know precisely where to focus. A comprehensive healthcare risk technology suite that includes patient safety and quality, risk management information systems and software (known as ‘RMIS’), and environment, health, and safety (EHS) solutions is ideal for addressing systemic problems because it helps an organization shift away from responding reactively and toward more holistic approaches. By accurately monitoring for specific causes/symptoms, hospitals can mitigate problems before they become huge concerns.

When patient safety data is utilized in support of a non-punitive culture and an organizational structure that limits silos of communication, healthcare organizations can pave the way for everyone to address root causes while still attending to immediate clinical concerns.